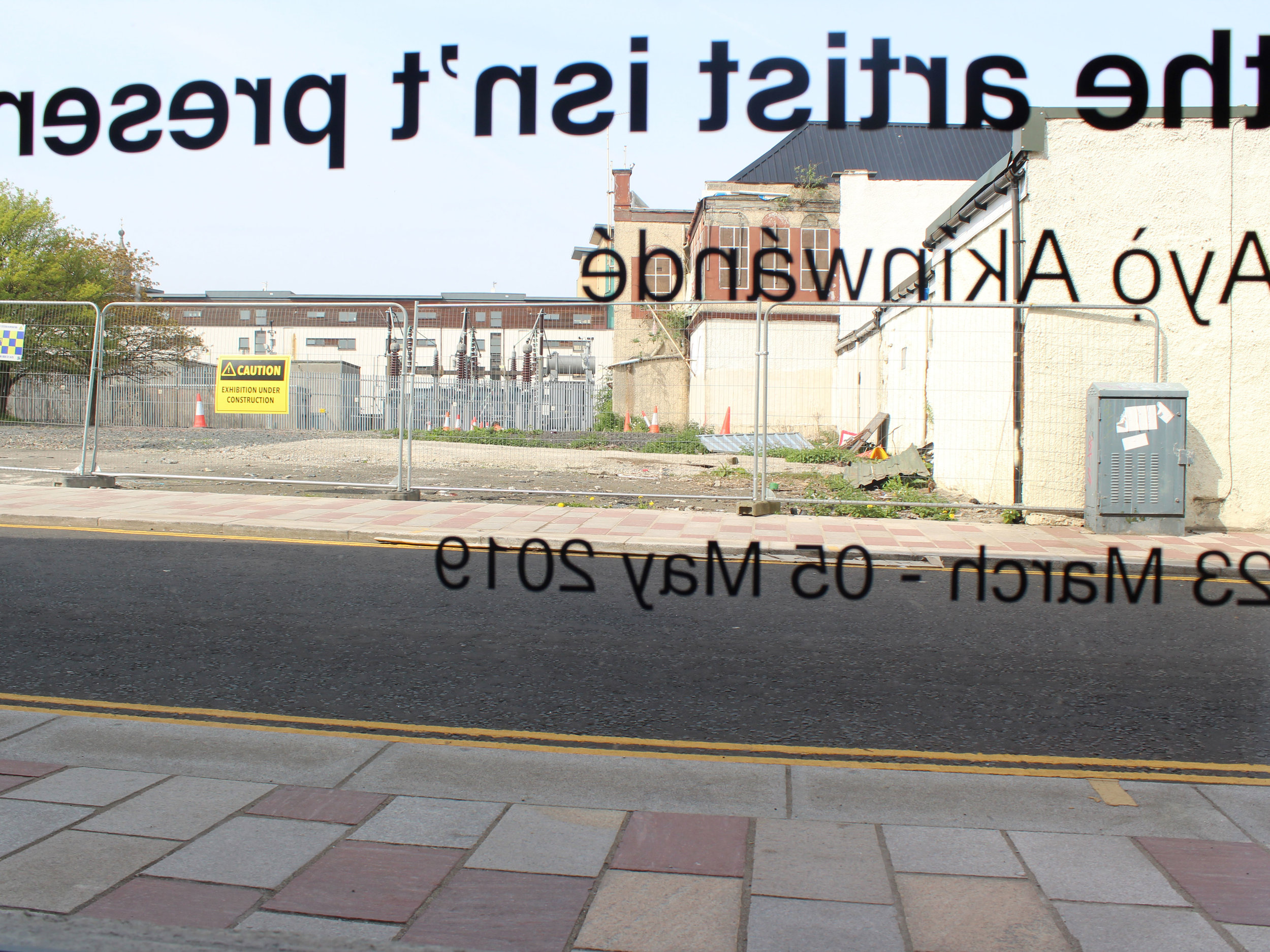

the artist isn’t present

Ayọ̀ Akínwándé

Curated by Natalia Palombo

23 March - 05 May 2019

Preview: Friday 22 March, 6-8pm

Ayọ̀ Akínwándé’s first solo exhibition in the United Kingdom borrows elements of building construction to explore the artist's own process of making new work. For the purpose of this exhibition, Akínwándé has interrupted the notion of completion, situating the viewer in his working environment. The exhibition is under construction.

This work stems from Akínwándé's background in architecture, incorporating design processes in the spatial sectioning of these ideas to evoke both intimacy and the monumental. Using materials found on construction site such as corrugated zinc sheets, wood, and stone, the artist mimics the restriction areas on construction sites to signify the invisibility of the artists’ process to their audience.

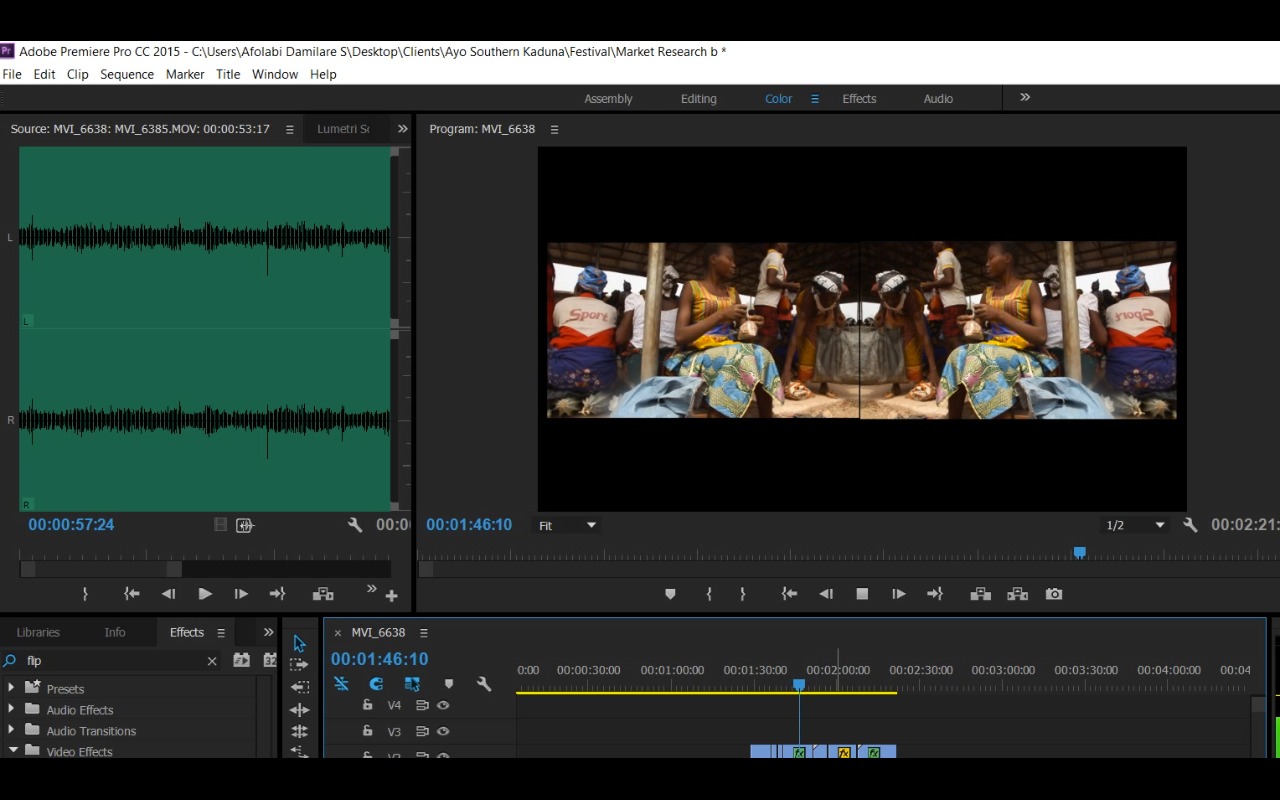

In amongst the rubble, the artist presents new video work based on his ongoing research into markets. The video explores ways of marking time across cultures, using the market system of the Igbos – in present day South-East Nigeria - as a starting point. The Gallow Gate is located in an original Barras Market building, and our geography and relationship to the largest outdoor market in Glasgow became a point of interest to the artist. As part of this research, Akínwándé travelled to various markets in the cities of Enugu and Abakaliki, places where he had spent significant time a decade earlier as a graduate.

In this body of work, the artist moves away from his extensive study into the power structures and vexed relationship between leadership and citizenship in Nigeria, whilst still closely considering the experiences of people in the built environment. Akínwándé’s work encompasses installation, sculpture, sound, video, photography and digital archives, to debate the Nigerian socio-political reality and the propagation of citizenship.

the artist isn't present applies the same satirical approach to exhibition making whilst disrupting the conventional relationship between artists and audiences.

www.ayoakinwande.com/current-the-artist-isnt-present

The Gallow Gate

Many Studios

3 Ross Street

Glasgow

G1 5AR

Thu - Sun

12pm - 5pm

Artist’s Statement

Note 1

”Who is showing at The Gallow Gate?”“Oh it’s an African guy- African artist, I can’t remember his name, I think you’ll like it, you should go see it”.

After 6 months of developing the first body of work, and then one month to turn it around and create something entirely new - that’s the beauty of this exhibition/installation - the beauty of collaboration between the artist and the curator.

With the video piece, and the entire exhibition at large, the question remains what does it mean for something to be complete, or incomplete. Maybe it is all a matter of perspectives.

Note 2

I think the greatest ‘gift’ of this exhibition is the fact that we wouldn’t have come up with this line of thinking without the visa issue.

When we talk about design being about creating solutions, does this mean we have created solutions to the visa issue through this exhibition. As an interruption - visa denial, forced us to think new solutions.

Maybe my presence isn't needed in Glasgow. Historically, commodities have always been more important and valued than the people. In this case, the art work, more important than the artist.

I’m conscious about how I’m being projected or/and received. As a Nigerian, an African, the question sometimes is “do you want to occupy the guests room in the art world’s mansion?”.

Note 3

The exhibition title as a metaphor statement.

Does the artist need to be present? This doesn’t answer anything, but rather poses questions to the audience.

Does the presence really matter when working in three-dimensional against two-dimensional forms? Or do things change?

For me, it’s about creating an experience for the audience. Is it enough for them to just see the work? Does the work itself do justice without me being there to engage the audience?

Does technology solve the problem of exclusion? Even some certain digital contents are blocked from my region - Nigeria.

If you Skype an artist into a room from an exhibition where they are denied access to attend, isn’t their absence magnified?

Note 4

It’s not much about the viewers opinion being reflected in the work, because work is made according to personal convictions not public opinion but your own personal thoughts are partly constructed by social narrative.

But does the audience really care about the artist’s process? Is it self indulgent for the curator and the artist to dwell in this idea of interruption. To the viewer, it could well be finished work. While for me, it is probably the beginning.

Exhibition making itself is a design process. Does it matter if the audience like what they see? Should I care if they understand? Should I just be happy that the work has been made?

Note 5

The exhibition itself is a visual representation of the significance of process and making work.

This could be true for artists’ process, building construction process, and/or design process. You have the freedom to make mistakes, to ‘control alt delete’ things, the freedom to undo.

Exhibitions have become moments where the artist seems to ascend into these ‘divine’ realms, but the danger in it is all of the flaws and frustrations that led to that exhibition becomes invisible to the audience.

Inviting the audience into the process gives the viewer the chance to make inputs, to ‘disagree’ with the artist in a way (constructively).

Curatorial Introduction

In early November 2018, I stood below a 27-foot looming figure in an art gallery 5000 miles away from Scotland. This sculpture (Ayọ̀ Akínwándé, The God-Father, 2018, wood, iron, fabric) provided a deeper understanding of the significance of monumentality in contrast to a very specialised and satirical narrative in Ayọ̀ Akínwándé’s practice. I arrived in Lagos at a very poignant time. Independence Day had not long passed, and political campaigns were beginning to stir, with just a few months until the next general election. My first visit to Lagos, above all, contextualised the presence and prominence of citizen agency and concepts of power structures that threads through Akínwándé's work.

Within 12 months, Akínwándé exhibited in three solo exhibitions and six group shows. The work in these exhibitions was rooted in his locality and closely narrated the vexed relationship between leadership and citizenship in Nigeria, making visible the legacy of colonialism and the performance of neo-colonialism, particularly in West Africa. We always understood that the reconfiguration of existing themes and methodology in his practice was an important process for creating new work at The Gallow Gate, as a means of negotiating a kind of creative and cultural profiling inherent in the western gaze. In other words, the work was to mitigate possible expectations that audiences may have of an “African artist” to address our history of colonialism for us.

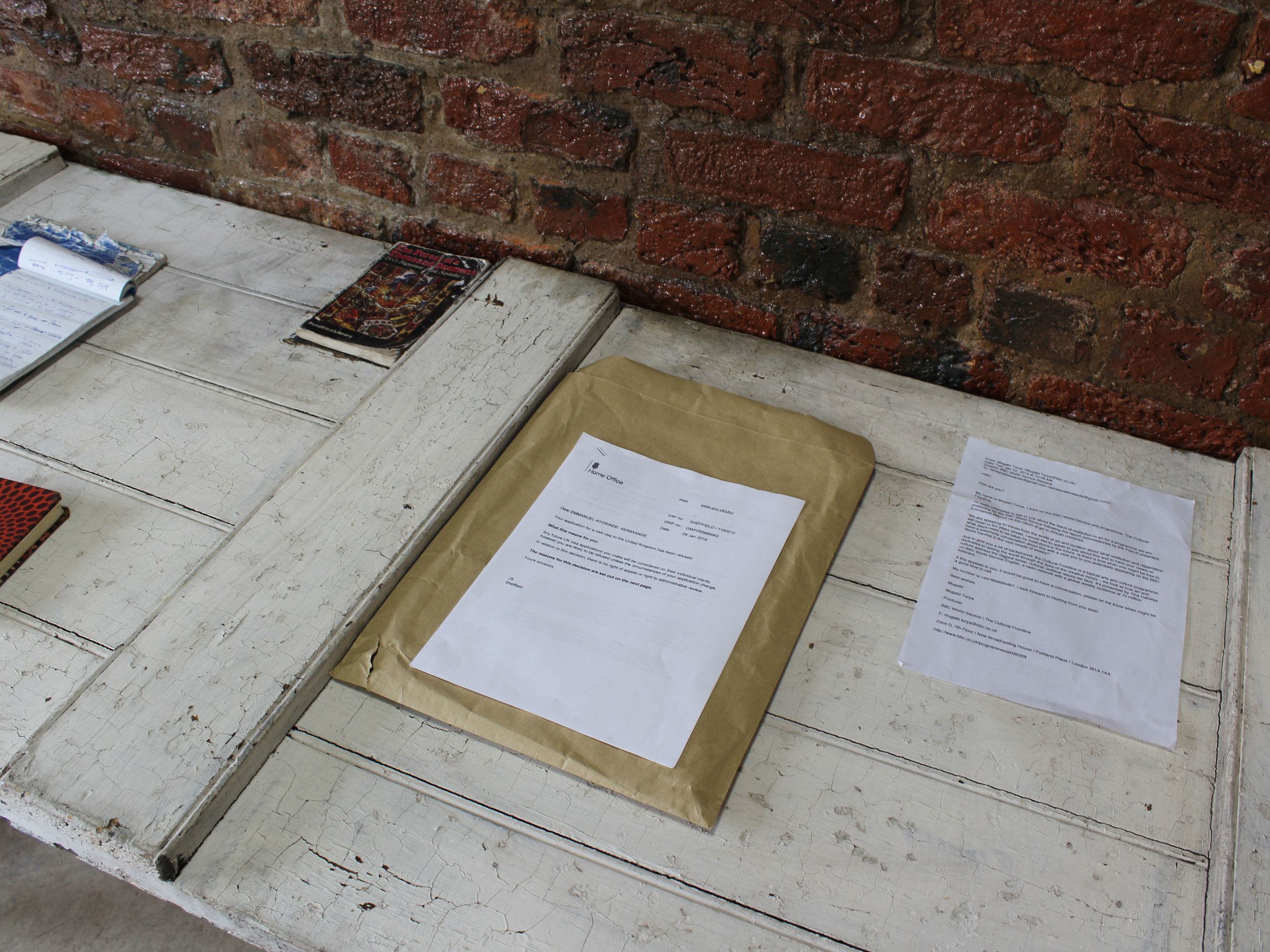

The Gallow Gate is located in an original Barras Market building, and our geography and relationship to the oldest outdoor market in Glasgow became a point of interest to the artist since exhibiting as part of a group exhibition at The Gallow Gate in March 2018. Working towards a solo presentation, Akínwándé began to focus his research on how outdoor markets have been used as a way of marking time across cultures, using the market system of the Igbos – in present day South-East Nigeria - as a starting point. In January 2019, Akínwándé travelled to various markets in the cities of Enugu and Abakaliki, places where he had spent significant time a decade earlier as a graduate. In 'Nkwagwu I', we are transported to mainland Lagos and the sound of the generator fills the room. Our senses are tuned to Akínwándé editing footage while talking to his colleague. We hear the artist convivially discuss topics such as the nature of the marketplace, the film medium in contemporary art, and his experience spending time in the north of the country. His field notes have been left beside the computer - a list of produce from Enugu and Abakaliki market detailing the initial offer and the final cost. This process of bargaining is a way of selling and buying at the Barras Market, and the notes were intended to be performed as part of an intervention in Glasgow. In this setting, an irony that is applied in all elements of the exhibition due to the artist not being present is made visible. In this case, the market notes could be here or there, but the installation within the space evidences the distance between the two cities.

Standing robust, a series of five reconditioned, corrugated metal sheets punctuate the room. The material stands along a grid, with separate objects parallel to one another. 'Onípáánù I' is a study of materiality and a direct nod to Akínwándé’s background in architecture, incorporating design processes in the spatial sectioning of both his ideas and in relationship with other works. Corrugated metal sheets are commonly used to create enclosures and to protect materials of value -expensive equipment on building sites, for example, or people in ‘temporary’ houses. In this work, Akínwándé appropriates the material to discuss the invisibility of artists’ processes to their audience; but also, in parallel, 'Onípáánù I' forces the audience to consider our perceptions on value. The metal sheet plays a pivotal role in the built environment yet it is disregarded as non-precious. In this setting, the material becomes an object of beauty. Sitting at 5, 6, 10, 13 feet tall, in a room that is itself 13 feet tall, the material is statuesque.

Weaving through the sheets, text appears both as instruction and as an implicit yet sinister reminder of the current political landscape of the United Kingdom. "Strictly no admittance to unauthorised personnel” is borrowed directly from the construction site, and as in ‘Onípáánù I’, this language creates a parallel between the construction environment and the artist’s process of making work. However, in the company of the documents scattered across 'Work-station' contextualising the artist’s absence, these words, cemented onto a corrugated metal sheet at the entrance of the room, occupy a new, political space. In this sense, they ring as a reminder of privilege or lack thereof. Not diverting from the original reference, this is deeply rooted in artist’s process of making work, creating a window into the impact that structural oppression has on the ability to move freely. For an artist, freedom of movement is currency.

the artist isn't present has inverted the monumentality prevalent in Akínwándé’s work, magnifying a microscopic element to art making. The exhibition still evokes a similar intimacy that is created by standing nose to knee to stern political figures, but this time we are in the intimate space of the artist's mind; a place we should perhaps not be in at all.

"It's not much about the viewer's opinions being reflected in the work, because work is made according to personal convictions not public opinion but your own personal thoughts are partly constructed by social narrative". Through the artist's own, hand-written reflections, we are reminded that people will bring their own lived experience to the reading of these works. Within an hour of installing the exhibition, someone spoke to me about the use of corrugated metal as a symbol of protection, “putting your arm over your workbook in school”. Another colleague circled the exhibition and upon leaving, shared that they understood the material - which is most commonly used to secure a site - as a social and political symbol of hostility.

For us, this is a layered conversation. We continue to understand the exhibition through the experience of the viewer. The exhibition is a reflection of no singular train of thought. Rather, it is a twelve-month long conversation around art making - and, by force, a three-month conversation on how to entirely reconfigure the exhibition to allow for the artist’s absence. As if 'giving away the answer', the focus was on materiality - the freedom to make whatever the artist wants despite expectations and obstructions faced on the basis of creative and cultural profiling. The letter Akínwándé received from the UK Government is simply a quick way to describe that the artist isn't present.

"Maybe my presence isn't needed in Glasgow. Historically, commodities have always been more important and valued more than the people. Is this case, the art work, more important than the artist"

Satirically signed, Ayọ̀ Akínwándé [excerpt from ‘Work-station’]

Biographies

Ayọ̀ Akínwándé is a contemporary artist born and based in Lagos. Akínwándé’s practice is multi-disciplinary, experimenting with lens based media, installation, sculpture, performance and sound to explore concepts of identity, duality and the multi-faceted layers of the human reality.

His artistic process involves constant monologues and dialogues on socio-political realities in his environment while the subsequent presentations incorporate architectural processes in a spatial detailing and sectioning of these ideas and thoughts to evoke both intimacy and the monumentality.

Akínwándé co-curated the 2017 Lagos Biennial and was also a participating artist at the exhibition held at the Nigerian Railway Museum. He was selected for the 2nd Changjiang International Photography and Video Biennial and was part of the “Chinafrika-under construction” exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Arts, Leipzig. In 2019, he presented solo exhibitions in Scotland, UK, and as part of the 13th Havana Biennial in Cuba.

He is a contributor to the book “ASIKO: On the Future of Artistic and Curatorial Pedagogies in Africa” by the Centre for Contem- porary Arts Lagos. His works and writings have been featured in Art Africa, Dienacht Magazine, PoetsArtists, Contemporary&, The Sole Adventurer, SomethingWeAfricansGot and other journals and publications around the world.

Akínwándé is a 2018 ArtX Prize finalist and a Top10 finalist at the 2018 ABSA L’Atelier Art competition with his work forming part of the exhibition at the ABSA Gallery. In 2019, Akínwándé will undertake three prestigious residencies: Place Publique (Darling Foundation) in Montreal, Canada; Hangar in Lisbon, Portugal; Factoria Habana for the 2019 Havana Biennial in Cuba.

Natalia Palombo is an arts producer with focus on contemporary visual art and film. Her research is centred on critical and convivial conversation in the arts, addressing issues of access to creative and cultural activity, expectations within arts practice, and creative outcomes in areas of regeneration. She works collaboratively in her practice, building partnerships and links to traverse critical subjects and activity within the sphere of contemporary art, its market, institutions and independent art spaces.

In 2011, Natalia co-founded The Telfer Gallery, and sat on the curatorial team until 2013. From 2013 – 2016, she worked in a freelance capacity as an arts producer collaborating with organisations internationally, including; British Council, World Design Capital, Pidgin Perfect, Mother Tongue, Hospitalfield, British Council Nigeria, Connect ZA, The Ar(t)chive, Bushveld Labs, Department of Arts and Culture South Africa, National Film and Video Federation (South Africa), Ministry of Arts and Multiculturalism (Trinidad and Tobago), Visiting Arts. During this period she was also part of the managerial and directorial team at Africa in Motion Film Festival.

In January 2016, she took up the position of Managing Director at Many Studios, where she is also curating a multi-disciplinary arts programme in the east end of Glasgow.

www.manystudios.co.uk

www.thegallowgate.art

www.nataliapalombo.co.uk

This exhibition is supported by The National Lottery through Creative Scotland and Diversity Art Forum.